I’ll hazard a guess that you’ve used the subtitle button on Netflix perhaps more times than you’d care to acknowledge. Whether you are deaf or hard of hearing, perhaps the oven fan is a little loud, you could be ESL, it could be late at night, or you have auditory processing issues – the use-cases are endless and indiscriminate: and the fact of the matter is that closed captions are useful and beneficial, both for those who are disabled and those who are not.

This is reflected in Ofcom’s 2013 study into accessibility and television, which found that seven million people used subtitles to watch television – though 6.5 million of those people were hearing. More recently, research in October 2021 revealed that 67% of the public sometimes finds it difficult to hear what is happening when watching TV or live performances.

Indeed, when exploring the future of social platforms and influencer culture, it is often beneficial to refer to how our terrestrial predecessors have managed such feats. Social platforms are reputationally a ‘Wild West’, with their evolution happening far faster than regulators have had time to catch up to. But with social consumption absorbing the real estate that terrestrial television once held, it’s vital that accessibility regulations are considered for social, in a similar way to terrestrial media regulation.

Currently, Ofcom requires that after five years of an applicable date, a broadcaster should ensure that 60% of their content is subtitled. After 10 years, the figure increases to 80%. I would love to explore a like-for-like comparison for social video platforms, but I’m afraid that no such regulation for this exists yet.

So close, but are we still too far?

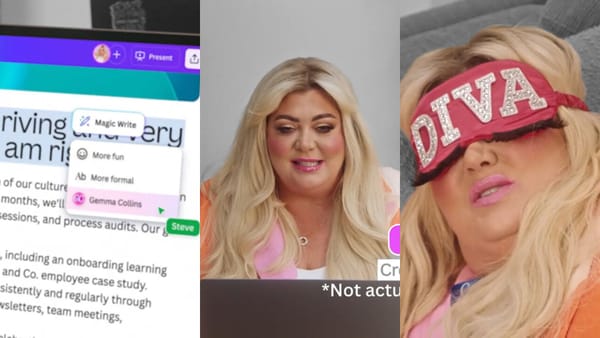

So, should we be congratulating platforms for doing the bare minimum? Especially when their ‘solutions’ are imperfect ones? I ponder this as Instagram continues to roll out its native auto-captioning functionality to Instagram Stories. Meanwhile, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook have all introduced similar auto-caption features to their social platforms over the years in varying forms.

Indeed, it is a great triumph of technology that auto-captioning has become so sophisticated that it takes a mere few seconds for dynamic captions to be transcribed, timed, and applied to a clip you have just recorded. It is a far cry from the early days of YouTube’s auto-transcription service, which provided far more merit in entertainment than perhaps of practical use. Yet frustration surely ensues when we recognise that now the technology exists, it is the execution by design that is still lacking.

Creativity within content is key, but in some instances function over form is preferred. Compared to other platforms, Instagram’s native captioning feature offers a variety of fonts, colours, and combinations for you to include accompanying copy with. But with this feature comes a lesser consideration of the benefits of consistency when producing captioning tools – it just takes one creator to add their subtitles in a low-contrast font colour for the effort to be inclusive to essentially be rendered useless. The road to hell is paved with good intentions, is it not?

Subtitles benefit us all

If uncertain about subtitling as a whole, take a step back and tune into the voices of the deaf and hard of hearing communities, who have been campaigning for better-closed captions since the dawn of social content. And still, if sheer accessibility and inclusivity is not a persuasive enough reason to caption your content (re-think that opinion – 22% of the UK population is made up of disabled people!), then perhaps Jessica Kellgren-Fozard’s impassioned plea – with the angle that including captions also increases your earning potential – may convince you.

It’s worth noting that the wider community can benefit from accessibility tools like captioning, too. The way that younger generations consume social content is different from their parents. They scroll faster, they double and triple-screen, and crucially, they consume adaptively to their environment: if they are in a social setting, they’ll consume on mute. If they’re walking with headphones in, they’ll only listen. If your content is not wholly deliverable by these mutually exclusive means, you are experiencing wastage. Whilst this is an important consideration for organic content creation, for paid material it is absolutely vital, when every penny of potential should count.

Unfortunately, we will always fall down when the onus of utilising tools of inclusivity is placed upon the Creator, rather than being platform-led. When platforms like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter have an elegant closed captioning feature that can be toggled on and off, Instagram and TikTok’s solution is creator-led, giving them the ultimate control over whether to caption their content or not, despite how easy the tools are to use. Now, instead of giving consumers a blanket tool to turn on an option to consume ALL content with closed captions, instead, it now creates a myriad environment, with a roulette of whether the content will be consumable to them or not.

So, yes – influencers should be subtitling as standard. It’s now easier than ever, takes very little effort, and has benefits that extend far beyond the surface level. Anything influencers can do to help make the web a more inclusive place for disabled people is only a good thing.

But also yes – platforms need to offer caption-assisted consumption modes as default, despite the influencer’s own preferences, and to combat sub-par execution.